Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

At The Taste Journal, we believe the secret to outstanding recipes isn’t found exclusively in the kitchens of world-class restaurants – it is found in the curiosity of the traveller, the patience of a historian, and the dedication of a home cook. We are here to bridge the gap between the historical origins of food and the geographical development of recipes refined through experimentation and culinary exploration. Our recipes are simple to make at home and focus on accessible ingredients found around the world; even a novice can create an outstanding dish in the comfort of their home.

If you really think about it, recipes are more than just measurements and instructions. They are heirlooms of human survival and resourcefulness. Food is a living record of where our ancestors have been and the mountainous, rugged peaks they have scaled. The history of civilization reflects the development of cultural diets and migration across time.

Long before the Silk Road, countries developed in direct response to what was available to them. This regional availability of produce didn’t just define what people ate; it defined their cultural identity. In the cradle of humankind, Africa was shaped by the paradox of its landscape. In Egypt, the predictability of annual flooding gave rise to a society centred on baked goods.

This flooding was called the “inundation” or “akhet” in Coptic. This yearly event was considered the heartbeat of Egyptian civilization. As a result of the inundation, an Egyptian society centred on baked goods emerged. During that time, Emmer wheat and barley were the primary grains consumed.

The geography of Sub-Saharan Africa reflects its diversity, ranging from the humid rainforests of the Congo Basin to the hot, arid savannas of the Sahel. The scarcity of water in this region led to the dependence on hardy grains such as millet and sorghum.

These grains were drought-resistant, allowing tribes to survive, primarily because their diets were rooted in starchy fruits and root tubers, which gave many African stews their distinct earthy flavours.

The landscape in Southern Africa includes vast temperate grasslands (the Highveld) and arid deserts, such as the Kalahari. During the Age of Discovery in the 16th century, the Portuguese introduced Maize (Mealies), native to Mexico, and it quickly became a staple among the Bantu-speaking people.

The lush land allowed cattle and other livestock to thrive, and meat protein became a core part of the indigenous diet. In the expanses of the Kalahari and the Karoo, the Khoisan people, including the San hunter-gatherers, perfected their diet based on the botanical abundance of indigenous plants. The Khoisan discovered over 300 to 500 different edible plants.

In China, there are culinary differences between the North and South. The Qinling Mountains and the Huai River separate the two regions. Northern China features a cold, dry climate, with a wheat-based diet of noodles and wheat-flour dumplings that require a specific skill to make the dough elastic, ensuring the dim sum is chewy. The Southern parts of China have a completely different diet influenced by their location and environmental factors.

China’s massive population meant that fuel in the form of wood and coal was always scarce. These ecological factors gave birth to the Wok. By cutting food into small, uniform pieces, Chinese cooks could stir-fry dishes in minutes. The Chinese domesticated rice over 9000 years ago. It was during the Song dynasty that they discovered a Vietnamese variety of rice called Champa, which matured in 90 days, unlike other varieties, which took 150 days.

The abundance of rice in China did not just happen, it was as a result of thousands of years of engineering. The Chinese had a geographical advantage that worked in their favour: the availability of land for rice paddies, however high-yield crops require precise water management. Once the correct ratio was established, this led to an abundance of rice and resulted in a substantial shift in farming. The Chinese were able to double food production per acre. This led to a rapid expansion in technological advancements within the Country and resulted in countless ingenious inventions such as the rice terraces, seed drill, winnowing machines and more.

In West Asia, we encounter Iran (Persia). In a naturally dry region, they engineered the Qanat, underground canals that brought snowmelt from the mountains to the plains. This incredible ingenuity created lush harvests and made Persia the world’s Fruit Basket, with exotic ingredients such as pomegranate, walnuts, and saffron growing in abundance. The Qanat led to the development of sophisticated recipes with a distinct identity. Persian cuisine is among the most refined in the world. These recipes were created in the royal courts of ancient empires, such as the Achaemenids and the Sassanids.

The hallmark of Persian cuisine is its reliance on the medicinal properties of food, similar to those of Chinese, Korean, and Indian cuisines. These nations did not rely solely on food to satiate their appetites; they saw food as possessing healing power. For over 3,000 years, the goal of Persian cuisine was not only about flavour but also about restoring internal balance within the body. Persians believe that food has both a warm and cooling nature. Most iconic dishes, such as Fesenjoon, are pre-balanced to prevent illness, with walnuts providing heat and pomegranates adding cooling elements. Whereas Fish is considered cold, it is always served with hot herbs such as dill and garlic to prevent joint pain.

Korean cuisine is defined by the four tastes: salty, sweet, sour, and spicy. Most of the staples we recognize today are the result of meticulous fermentation and historical interactions with neighbouring empires. Ganjang is Korean soy sauce that is made from soybeans. The fermentation process results in soy sauce and protein solids; the remaining protein is extracted from the soy sauce and forms the basis of Doenjang paste. The Doenjang paste was considered a survival food during the winter months. This created the base for the iconic Doenjang-jjigae (Stew).

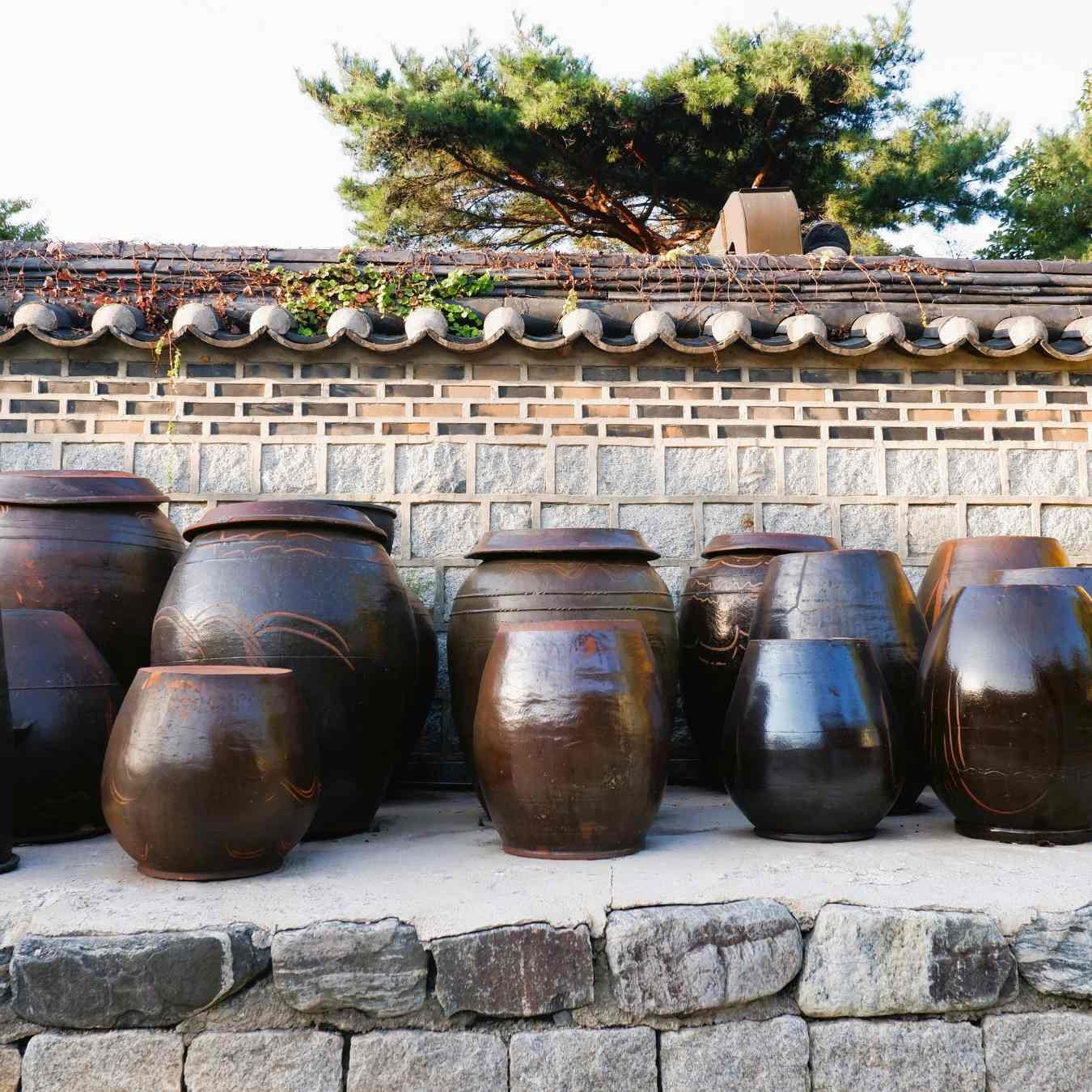

Lastly, Gochujang, a chili paste, is a thick, moderately sweet, and spicy paste made from chili powder, fermented soybean powder, barley malt, and glutinous rice. This chili paste forms the foundation for over 100 Korean dishes. The Black Earthenware jars, known as Onggi in Korea, are a popular feature. The micro-porosity of the jars allows for high-salt fermentation. These Earthenware jars are instrumental for storing Ganjang, Doenjang, & Gochujang.

Similarly, India has its own “Rice-Wheat Line”. In the Northern parts of India, the climate is arid, and as a result, wheat and dairy from the grazing cattle created a culture of ghee and tandoors. In contrast, the tropical South had a complete identity shift, with an array of coconut groves and rice fields. Even the variety of spices differs vastly between the Northern and Southern parts of India.

The principles of Ayurveda (hot & cold foods) are central to Indian cuisine. The northern parts of India are characterized by cold winters, whereas the southern parts have tropical, hot weather. The North relies heavily on warming spices, using higher amounts of Cumin, Cinnamon, Cardamom, and Cloves. Garam masala is considered a hot spice blend. Spices are often tempered with ghee and mixed with yogurt and nuts to create thick, comforting gravies.

People in the South of India believe that using hot spices induces sweating, which helps cool the body. Interestingly, a similar concept exists in Korean culture, it is called ”iyeol chiyeol”, to fight hot with hot and cold with cold. South Indians use Mustard seeds, Curry leaves, Tamarind, Black pepper, and Dried Red chilies in their curries. Coconut oil and milk help balance the heat of the chilies.

The Desert and the sea shaped the culinary world of neighbouring Arabia. Dates and camel milk ensured survival in the Desert, and the coastal cities became the world’s spice hub. The maritime trade combined cardamom, cloves, and saffron into the Arabian masterpieces. The Arabs were quick to adopt spices from the Silk Road. Did you know that there are 300 varieties of dates that grow in Saudi Arabia?

One of the most popular dishes from Saudi Arabia is Kabsa, which can be made with Chicken, Lamb, or Hashi, which is young camel meat. It is said that young camel meat is a cross between beef and lamb, and that it has sweet, and savoury undertones of flavour.

While the cuisines of the UAE and Saudi Arabia share Bedouin roots, they are different in certain aspects. The two countries share a similar national dish, but the taste varies in each country. The Saudi Arabian Kabsa uses more tomato paste, giving the rice a rich, deep red color. The dish is also topped with fried onions, pine nuts, and raisins. Black limes are a key ingredient of Kabsa.

The Emirati Machboos uses less tomato and more Bezar (a blend of spices: peppercorns, cumin, ginger, cinnamon, and coriander). Both dishes use different cooking techniques, with the kabsa cooked in one pot. Whereas the machboos cooks the meat with whole spices, then browns it separately. Moreover, Emirati Machboos is available in a seafood version with local shrimps. In the Emirates, Luqaimat are called “Little Bites“. They are crunchy, golden-brown donuts that are not sweet; on the inside, they are soft and airy. The outside of the luqaimat is coated with date syrup, making this a balanced dessert. The UAE considers pairing Luqaimat along with Gahwa (Arabic coffee) as a symbol of Emirati hospitality. Interestingly, the traditional coffee in the UAE is not sweetened with sugar.

The Spirit of the Silk Road extended to Central Asia, and the nomadic tribes of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan built their kitchens on the move. The tribes from these countries were quick to incorporate spices from the Silk Road. Taking with them a large cast-iron cauldron, a clay oven, and a medley of herbs such as cumin, dried chili, coriander, and barberries, they created dishes such as Plov and Manti. On the other hand, the Mongols maintained the natural flavours of their food, which centred on red meat, fat, and dairy.

In the high, arid steppes of Mongolia, farming was difficult due to environmental challenges. Interestingly, only 1% of Mongolian land is suitable for crops. The Siberian Anticyclone causes drastic weather changes. In summer, Mongolia experiences intense heatwaves, whereas in winter, it can be icy cold. Crops require an average of 150 frost-free days; however, drastic weather shifts are standard. Unseasonal frost can occur in the midst of summer; this is the primary reason why Mongolians adopted a high-protein, dairy-rich diet.

The Turkish people are initially from the Steppes of North-East Asia. Turks have lived in Anatolia for 900 years. They were originally tribal, living in the region near the Mongols, Siberians, and Manchus. The Turkish cuisine and diet experienced rapid changes as they migrated from the steppes to Anatolia. Turkish cuisine is often called the bridge between continents. During the Ottoman period, the Topkapi Palace hired hundreds of chefs, each specializing in individual crafts such as soups, sweets, and breads, refining nomadic dishes into Imperial standards. Competition was high, and the eagerness to please the Sultan was a keen endeavour; this led to the creation of many recipes, some influenced by other cuisines, such as Mediterranean, European, and Middle Eastern. Recipes from Syria and Iraq, in the form of kebabs and hummus, all made their way to Turkey, and others were customized for the Turkish palate.

In the Northern latitudes, Russian cuisine began in the forest and the rugged steppe. With short summers, they quickly became the world’s experts in food preservation and in foraging for mushrooms, berries, and honey. They used a slow-burning stove called a Pech to turn root vegetables, such as beetroot, into velvety Borscht.

The massive brick furnace played a key role in the creation of soups, stews, and porridges. The stove would be heated up to high temperatures in the morning and provide steady, indirect heat for hours, leading to a lifestyle of slow-cooking in which food languished in the receding heat. They developed recipes such as the nutrient-dense kasha and the flavourful soups called shchi, which were often prepared by placing ingredients such as cabbage and meat into a clay pot in the morning, and retrieving them, perfectly softened, in the evening.

One of the popular and ancient recipes of Russia is Blini (Pancakes), since the pancakes were round and golden in colour, it represented the sun and marked the end of winter. In the 1700s, Russian nobles began to add caviar onto their pancakes as a symbol of status. Dumplings arrived through the travellers, many believe it was the Mongols from Central Asia that brought the dish to Russia, the dish grew in popularity and it is now called Pelmeni. Dark rye bread was renowned for its ability to stay fresh through the long winters. Fermented foods such as horseradish, mustard, and dill helped to balance the richness of their foods.

Thailand is world-renowned for its meticulous balance of flavours. Most Thai dishes will have sweet, sour, salty, and spicy components. This Asian country has an interesting position in Asia; in the old days, it was pretty normal for Chinese, Indians, Portuguese, and Persians to visit Thailand. The Chinese introduced the wok to Thailand, which helped local people develop many noodle dishes of their own, such as Pad Thai.

Indians and Persians added various spices to Thai cuisine, such as cumin, turmeric, and coriander seeds. Instead of using dairy products like ghee and cream, Thai people use coconut milk, which gives the curries a lighter flavour. Coconuts also grow in abundance in the region. Many people are unaware that the Portuguese introduced chilies to Thailand in the 16th century. The chilies added an extra layer of heat to Thai curries. Thai dishes have their own identity, featuring lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir Lime leaves. These core components, along with Palm sugar and Fish sauce, give Thai food a unique flavour.

There are many types of foods that are available in America, even though hamburgers, hotdogs and pizza are favourite dishes, there are also other cuisines that have played an important role in the country. Apart from Italian, and French, you can easily find many different types of Asiatic dishes, Mexican, Middle Eastern and African dishes in the country.

Italy and France are considered the pillars of the European culinary world. Italy’s cooking philosophy is the “Mother of Simplicity”, and France is the “State of Technique. The two cooking crafts are different, yet both produce incredible dishes. The Italians are known for Pizza and Pasta. At the same time, the French have baguettes, an array of pastries, and many different types of soup. There is a stark contrast in how recipes were formed and shaped, with many Italian dishes having ‘tenant farmer‘ roots. Conversely, French cuisine was shaped in the Palace of Versailles, where the Kings turned dining into political plays of dominance.

When Christopher Columbus returned to Europe in 1492, he took with him potatoes, tomatoes, corn, cacao, vanilla, and pumpkins. This journey was instrumental in shaping European cuisine. If not for the tomatoes from America, Italians would never have started making tomato pasta and pizza. Chocolate and Vanilla also form core components of many European dishes. When European settlers began travelling to the New World (America), they brought wheat, sugar, coffee, grapes, cows, and sheep. The steak-heavy diet would not be possible without European livestock.

The story of humans, diet, and history provides a fascinating look at the development of cultures. It serves as proof that no flavour exists in a vacuum. Every recipe is a record of people’s endurance and their ability to harness the produce found in their environments. To eat a traditional meal is to consume a story of adaptation, survival, and migration. The relationship between people and their cultures remains forever preserved in their recipes.